You may struggle to picture in your mind what a lemon shark is or why it matters. I completely understand, as most of us live nowhere near the ocean and, even if we do, we have so much going on in our lives it seems trivial. What may surprise you is that the lemon shark is one of the most accessible sharks in the world! We should know what it is, allow me to introduce you:

Where do lemon shark live?

Most lemon sharks live in the western Atlantic ocean (the eastern coast of the Americas), from New Jersey to Brazil. They have been found in the eastern edge of the Pacific as well (the western coast of the Americas), from Ecuador to the southern parts of Baja California, Mexico.

Lemon sharks also live on the west coast of Africa. They were once abundant in the sea of Cortez, near Brazil, and along the west Coast of Africa especially around Mauritania.

In the last 50 years, lemon shark numbers have dropped an estimated 50-79%. Now they are rarely seen except in the Bahamas and along the coast of the United States where they are not over-fished to such a degree.

What makes them so accessible?

- They remain in and return to the same shallow coastal areas, referred to as their nursery grounds. This means they can be reliably found and monitored in consistent locations.

- They can survive better in captivity than other sharks, such as the great white and mako. This allows researches to study them in more depth and detail than other creatures, such as the great white and mako, who cannot survive in captivity.

What do lemon sharks eat?

Lemon sharks eat

- fish,

- rays,

- crustaceans

- smaller sharks (including smaller lemon sharks)

Fish makes up the larger portion of this diet and, like other sharks, the lemon shark is most active at night. They tend to prefer hunting by stalking rather than ambush tactics, choosing slower prey and being more intentional in their diet than opportunistic feeders such as tiger and bull sharks. Not all sharks eat the same way: some roll in a circular motion, some grip with the upper jaw and slice with the lower; the lemon shark grips with both jaws and then thrusts its head side to side until a piece of flesh rips off.

Bonus Fact: The biggest lemon shark ever recorded was 11.3 feet and 405 pounds. An average adult grows closer to 9 feet and 200 pounds.

Lemon sharks live in relatively shallow, warm tropical and subtropical water along the coast, usually not going beyond depths of about 260 feet. The smaller, younger sharks tend to stay closer to the shore and in mangroves, where they are protected from larger predators, including sharks, who may seek them out as prey. When grown, they move to deeper water.

They cannot survive in fresh water, such as lakes and rivers, like the bull shark. Even so, you might see them in a river. How? Lemon sharks are more adaptive to salt levels than some other species. They cannot survive in fresh water; they can, however, survive in brackish water, the water towards the end of a river that is not quite fresh, not quite salt water.

Reproduction:

Some sharks have the unusual ability to reproduce asexually, we believe, as seen in a hammerhead in a Nebraska zoo in 2001 and a zebra shark in an Australian aquarium in 2017. The lemon shark, however, reproduces through intercourse like most animals, reaching sexual maturity at around 12-16 years old. Females only mate every 2 years, though with multiple males at a time, and can store the sperm for several months; gestation lasts an entire year, so it is a big deal when the 24 inch pups enter the world.

This somewhat slow rate of reproduction combines with lemon sharks’ reliably consistent choices of location to increase the threat to their population. They are easy to find and slow to restore, having a maximum of around 13 pups every 2 years. Though that seems like a lot, many (probably most) will die before they reach adulthood.

Although they carry and give live birth to their young, lemon sharks (like all sharks) are not mammals but exceptional fish. They do not produce milk to nurse their young, they are cold-blooded, and they have no hair.

How do you identify a lemon shark? 3 best indicators:

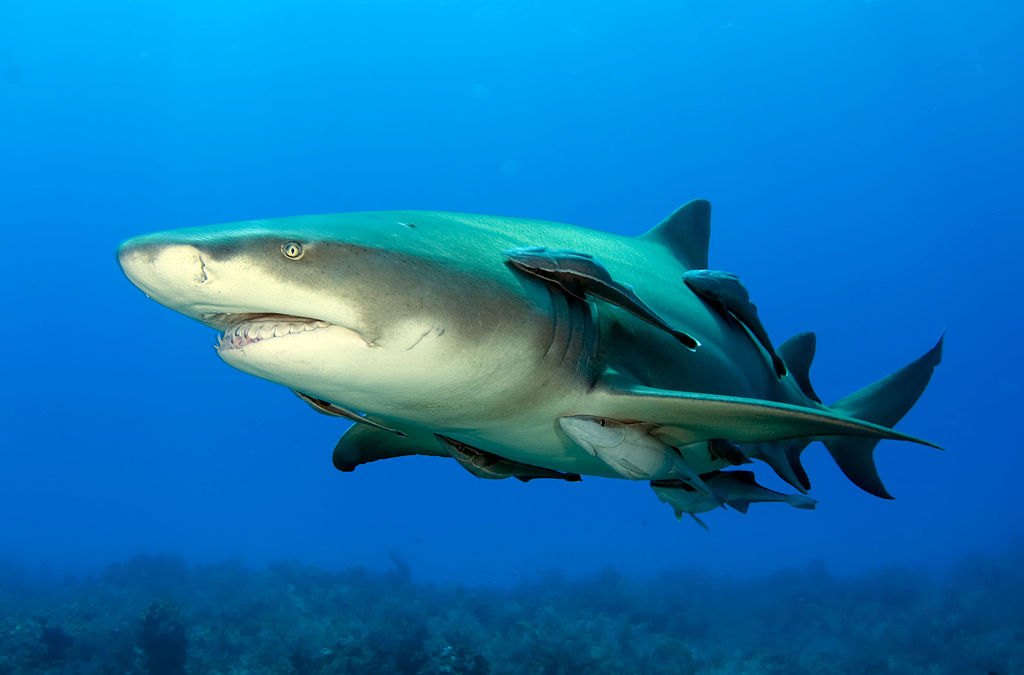

- You can identify a lemon shark by its 2 dorsal fins, almost equal in size. Many sharks have two dorsal fins, but for most the one towards the back is significantly smaller. Looking from the side you can see that the first of these dorsal fins does not start until after the back of their pectoral fins, the ones on the sides.

- Looking at the snout can also give you a clue: they have a short and blunt snout, not pointed like the mako’s.

- Another indicator to identify a lemon shark is the yellowish hue in the coloring, darker and nearer to brown on the back with a very light yellow on their lower side. This yellow color is why they call it a lemon shark, because it somewhat resembles the color of a lemon. The purpose of this coloring is camouflage, helping them to blend in with the sand of the sea floor, a useful adaption for a species that spends much time in the shallower coastal waters.

You can identify a lemon shark by its 2 dorsal fins, almost equal in size.

Interaction with humans

The lemon shark was not necessarily discovered, but first recorded in 1868 by Felipe Poey, a Cuban zoologist. He first named it Hypoprion brevirostris but renamed it Negaprion brevirostris.

As far as we know, a lemon shark has never killed a single person. We have 10 recorded bites, none of them fatal. Certainly a lemon shark can hurt you and can even kill you if it wanted, though under normal conditions this is unlikely. They are not the most aggressive species, nor the most gentle, but somewhere in the middle and are a species some divers seek out to swim with and photograph.

As far as we know, a lemon shark has never killed a single person.

A group of divers in Florida (the Emerald dive team) developed a special bond with a particular lemon shark, which they named Blondie. According to them, when they went down on a dive, Blondie would rush to meet them, looking for a rub on the snout. They wisely recommend not to expect this as the norm and to maintain caution around sharks which you have no prior relationship with, and other divers point out that some can be easily spooked.

Bonus Fact: a group of lemon sharks is called a “shiver”

Other divers have noticed that lemon sharks seem to compete for their attention, chasing away other sharks to have exclusive time with the humans.

Lemon sharks do not only make “friends” with humans. This article from the National Geographic describes how biologists tested lemon sharks at the Bimini Biological Field Station in the Bahamas. They found clear evidence that lemon sharks show a very social side and can even learn from each other, though when they group they tend to gather with sharks of a similar age and size. This grouping according to size makes sense as a means to safety considering that larger lemon sharks sometimes cannibalize the smaller ones.

The sicklefin lemon shark.

Like their American (and west African) brethren, sicklefin lemon sharks prefer shallower water and tend to stick around the same areas consistently.

They are nearly identical in many ways but can be differentiated by the shape of the fins. As the name suggests, the sicklefin lemon shark has fins (particularly the pectoral fins) that tend to sweep back in a way that resembles a sickle. Our OG lemon shark has a more triangular shape to it’s fins.

Divers can swim with this species provided a respectful caution is taken. If agitated they can become violent, something more likely with younger sharks and encounters with fishermen. On the other hand, in French Polynesia tourists come to dive with and feed them. As long as both professional and common-sense precautions are taken, they are a safe species to dive with and not a high threat to humans.

Sicklefin lemon shark habitat stretches along the coastline from South Africa all the way up into the Red Sea and then eastward around India to the tip of Thailand. From here it expands across Indonesia, to the north coast of Australia and scattered islands in the west Pacific.

Fishermen in India and southeast Asia are pushing the sicklefin lemon shark to extinction. Populations have already been wiped out near India and Thailand, and are extremely scarce in Indonesia. In Australia, in contrast, populations are healthy.

Fishermen in India and southeast Asia are pushing the sicklefin lemon shark to extinction.

The sicklefin lemon shark was not discovered, but first described by the German naturalist Eduard Rüppell in 1837, who gave it the name “Carcharias acutidens,” though it was later renamed “Negaprion acutidens.” You might notice acutidens in both names; acutidens means “sharp tooth,” and this shark is also known as the sharptooth lemon shark. The sicklefin may have been recorded earlier, but it is understood that the lemon shark of the Atlantic is more closely related to their common ancestor.

The lemon shark, both sicklefin and OG, is not yet endangered, as of August 2021, but it is listed as vulnerable (one step up from endangered) and on the decline. Lemon sharks are targeted by private and commercial fisherman for their meat, skin, and fins. You can eat lemon shark, and many consider it a delicacy. Consumers also use the skin for leather, and harvest the fins for shark fin soup. At this point, however, shark meat in general is not the most highly recommended of foods. Beyond the fact that their numbers are rapidly dwindling throughout the world, the meat is not entirely safe. As a long living predator at the top of the food chain, sharks have the highest level of mercury of any fish. Side effects of mercury exposure include headaches, tremors, and cognitive dysfunction.

Conclusion

There you have it, these lemons turn out not to be so sour after all. With 0 confirmed human fatalities and even some human friends, this apex predator is far from the worst thing you could encounter in the wild. They are another strange and beautiful creature, terrifying and humbling, powerful yet trepidatous. Thank you for joining me for this introduction to another marvel of the deep.